Great-Grandfather Guy Bedwell Trained 1919 Pimlico Oaks Heroine Milkmaid

BALTIMORE – On any given day, Clark Bedwell Shaffer Jr. is easy to pick out at the racetrack. Always nattily dressed in suit, tie and matching trilby, his clothing choice is a throwback to the heyday when such attire was as commonplace among racegoers as the champions they went to see run.

But Shaffer has more than just a smart-looking wardrobe. The Laurel, Md. native, who grew up just two miles from Laurel Park, has a familial link to Hall of Fame horseman Harvey Guy Bedwell, best known for his accomplishment as trainer of racing’s first Triple Crown winner, Sir Barton.

At the same time Bedwell, Shaffer’s great-grandfather, also trained a standout 3-year-old filly named Milkmaid, winner of the inaugural 1919 Pimlico Oaks. Renamed the Black-Eyed Susan in 1951, the race will celebrate its 100th running Friday at historic Pimlico Race Course.

“People will say, ‘That’s the guy that always gets dressed up at the racetrack,’ but they don’t necessarily know about my family history,” Shaffer said. “I think my great-grandfather would be proud.”

Shaffer, who turns 70 in August, is a retired system services technician at Loyola University in Baltimore and regular racetrack visitor, particularly to Laurel. The track is situated close to the old farm where Milkmaid and Hall of Famers Sir Barton and Billy Kelly trained, where his father grew up and eventually married Shaffer’s mother. Named Yarrow Brae, it was located on what is now a commercially developed plot of land off Route 1.

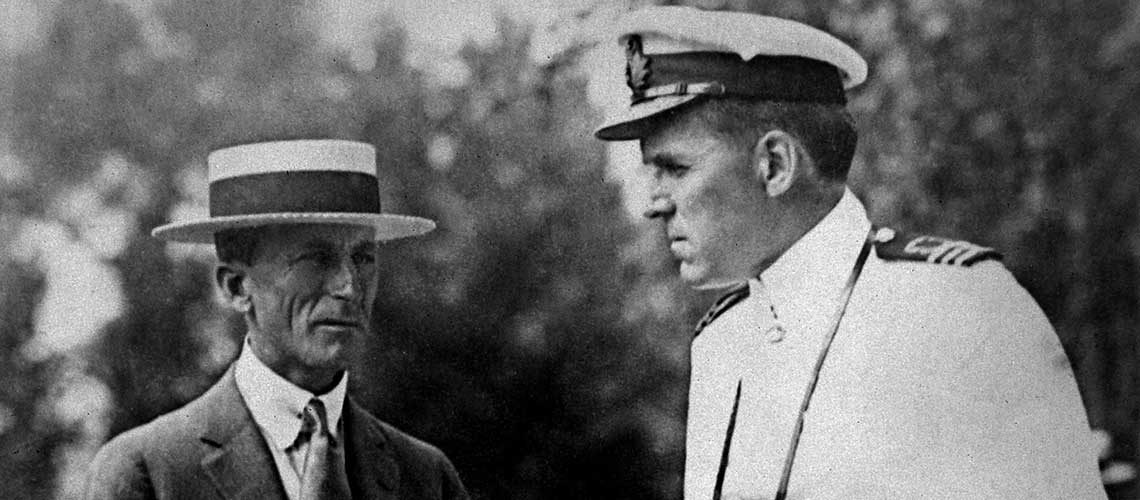

Largely training his own horses, Bedwell was North America’s leading trainer by wins seven times between 1909 and 1917, when he took over as trainer for Commander J.K.L. Ross, a wealthy industrialist whose father founded the Canadian Pacific Railway. Thanks in large part to horses like Milkmaid and her Hall of Fame stablemates, Bedwell was the top money-earner in 1918 and 1919.

Shaffer never met his great-grandfather, who passed away in 1951, and didn’t hear much of the family history from his father, who was only 52 when he died in the early 1970s. Much of what he learned came later from years of conversation and research including the book Boots and Saddles: The Story of the Fabulous Ross Stable in the Glory Days of Racing, published by J.K.L. Ross’ son, Jim.

“The book was about the Ross’s, but my great-grandfather was a supporting part of it,” Shaffer said. “He had been dirt poor. He did cattle drives at the age of 12. He lived on a horse. That’s how he knew horses so well, because he lived it from such a young age.”

Milkmaid and Sir Barton were purchased in 1918 from their breeder and original owner and trainer, John E. Madden, the only inductee to both the Thoroughbred and Harness Racing Hall of Fame. The price for Sir Barton was $10,000. Ross turned them over to his trainer, whose nickname – befitting both his initials and his tough upbringing – was ‘Hard Guy.’

“Milkmaid, around the barn her name was Daisy,” said Shaffer, who accepted the plaque on behalf of the family when Bedwell was inducted into the Racing Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. in 2015. “That’s what the stable hand that took care of her called her. He referred to her like she was an old girlfriend.”

Milkmaid was entered against males in the 44th Preakness Stakes, contested May 14, 1919 just four days after Sir Barton won the Kentucky Derby. A 1994 Sports Illustrated article titled ‘A Nearly Forgotten First’ indicated jockey Earl Sande, aboard Milkmaid, “was told to veer in at the start, break up the alignment of the field and allow Sir Barton time to get a good position.” Sir Barton didn’t need the help, leading all the way to win by four lengths, with Milkmaid finishing eighth in a field of 12.

Three days later, Milkmaid returned to Pimlico for its new race, the Oaks, created as a complement to the Preakness. The inaugural field, reduced to five by scratches due to rain and sloppy track conditions, competed for a $5,000 purse. The Daily Racing Form, in its May 18, 1919 recap, read:

“The race for the Oaks today was really only a dual contest. Two of them, Ophelia and Milkmaid, were the only two that could untrack themselves. Before a half-mile had been traveled it was plain that it was a two-horse race. Ophelia was the pacemaker and she led along the backstretch and until the far turn, where Sande sent Milkmaid along and challenged. The struggle was brief. Milkmaid looking in better condition than she did at Havre de Grace or in her start in the Preakness, went to Ophelia an eighth out and easily vanquished her. She won going away.”

Three weeks later, on May 31, 1919, Milkmaid ran second as the favorite to Lillian Shaw in the Kentucky Oaks, beaten a length, also running second in the Alabama at Saratoga. Other wins came in the Wilmington Purse, Bellair Handicap, Gazelle Handicap and Kenner Stakes during a season where she was named co-champion 3-year-old filly.

Milkmaid was just as brilliant at 4, named champion older female horse of 1920 following wins in the Ladies Handicap, Salem Handicap, Galway Handicap, Great Neck Handicap and Mineola Handicap.

According to statistics provided by the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame, Milkmaid had a record of 49-23-13-6 and purse earnings of $41,495, winning stakes in each of her four seasons of racing. She was retired to broodmare duty at Yarrow Brae, producing two foals by the stallion Cudgel, Ross’ champion older male horse of 1918 and 1919.

“There are some photos of my great-grandfather and my great uncle, my father’s uncle who was also a trainer,” Shaffer said. “They’re wearing the hats, the suits, the ties, and you think, ‘Who dresses that way now?’ I know where I get it from.

“Man, I wish one time I had been there with my father and my great uncle and my great-grandfather at the track, just one time, standing around with them and hearing how they all interacted,” he added. “I’ve always liked that. That’s [the best] part of the thing with the racetrack for me, just the people. The whole experience of live racing.”

One thing is for certain: either interaction, whether in thought or in reality, would not be complete without Shaffer’s signature chapeau.

“People ask me, ‘Did you always wear a hat?’ and I say, ‘No, I used to have hair,’” Shaffer said. “Once the hair went, my head started getting cold all the time. When you have hair, you didn’t want to wear a hat because it always got messed up. But now that I don’t have any my head gets cold, or it gets burned when its hot outside, so I need the hat.”

Story: Phil Janack

Photos: Keeneland Library, Maryland Jockey Club